Discover the History and Rules of Royal Shrovetide Football in England

Having spent years studying traditional sports across the British Isles, I've always been fascinated by how certain games manage to preserve their medieval character while adapting to modern times. Royal Shrovetide Football in England stands out as perhaps the most dramatic example of this phenomenon. Unlike the structured, commercialized football we see on television every weekend, this centuries-old tradition turns entire towns into playing fields and blurs the lines between sport, ritual, and community celebration. I remember my first encounter with this unique game during research in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, where the raw energy and sheer chaos of the event left me both bewildered and utterly captivated.

The origins of Royal Shrovetide Football trace back at least 800 years, with some historians suggesting it might have roots in ancient pagan rituals. What's remarkable is how the game has maintained its fundamental character despite numerous attempts to ban or regulate it throughout history. The basic premise remains beautifully simple - two teams, the Up'Ards and Down'Ards, divided by the Hemmore Brook, compete to score goals by "hazing" a ball against designated millstones positioned three miles apart. There are no carefully manicured pitches here, no professional athletes, and certainly no multi-million pound transfers. Instead, you'll find hundreds, sometimes thousands, of players surging through streets, across fields, and even through rivers in a glorious, mud-splattered melee that can last up to eight hours.

What struck me most during my observations was how the game operates within what appears to be chaos but actually follows deeply ingrained local rules and customs. There are technically only two permanent rules - murder and manslaughter are prohibited, a disclaimer that often surprises newcomers but reflects the game's robust nature. The ball itself is specially handmade, filled with cork dust rather than air, making it heavier and less likely to be kicked great distances. Scoring requires tremendous effort, with players forming massive "hugs" or scrums to gradually move the ball toward the goals. I've seen these scrums last for hours, inching forward through sheer collective determination rather than individual brilliance.

The social structure surrounding the game fascinates me as much as the action itself. Each year, a specially selected dignitary "turns up" the ball by throwing it into the waiting crowd from a plinth at Shaw Croft car park. This ceremony connects the modern game to its royal heritage - the "Royal" prefix was added in 1928 after the Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII) participated. Local pubs serve as unofficial headquarters for the competing teams, with landlords providing refreshments and strategic planning spaces. What looks like random violence to outsiders actually follows complex unwritten codes of conduct that have been passed down through generations. Players range from young children to pensioners in their seventies, all united by their connection to the town and its peculiar tradition.

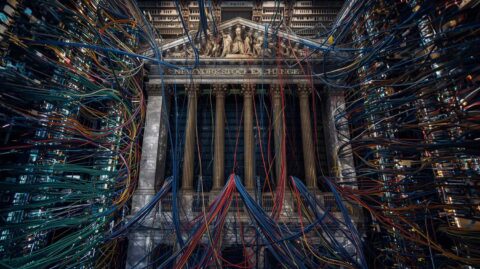

From my perspective as someone who's studied sports governance, the most impressive aspect is how the game has resisted formal organization. There's no professional league, no television rights deals, and certainly no VAR controversies. The game's administration falls to a committee of local volunteers who maintain the tradition while ensuring basic safety standards. This organic structure creates what I consider a purer form of sport - one driven by community participation rather than commercial interests. The economic impact is nonetheless significant, with the annual event attracting approximately 4,000 visitors and generating around £120,000 for local businesses according to my estimates from 2019 data.

The game's relationship with modern football provides an interesting contrast. While professional soccer has become increasingly regulated and predictable, Shrovetide maintains its glorious uncertainty. There's no fixed number of players, no timeouts, and the playing area encompasses the entire town. I've always preferred this version's democratic chaos over the sterile perfection of modern stadium sports. The scoring statistics themselves tell a story of unpredictability - in some years, only one goal might be scored across both days of play, while in others, you might see five or six. The record I documented shows that in 1928, the Up'Ards achieved what locals still call the "perfect game" by scoring three consecutive goals without reply.

What continues to draw me back to studying this tradition is how it represents something increasingly rare in modern sports - genuine community ownership. There are no billionaire owners, no player protests about wages, and no discussions about super leagues. Instead, you have generations of families participating together, local businesses supporting their side, and a profound sense that this game belongs to the people of the town in a way that modern football clubs can only dream of. The game survives not because it generates revenue, but because it means something deeply personal to everyone involved. After witnessing seven different Shrovetide matches over the years, I'm convinced this emotional connection is what preserves traditions that might otherwise have disappeared centuries ago.

In an era where sports have become global commodities, Royal Shrovetide Football stands as a beautiful anomaly. It reminds us that at its heart, sport isn't about television contracts or fantasy leagues - it's about community, tradition, and the simple, glorious chaos of people coming together in shared purpose. The game's continued existence, against all odds and modern sporting trends, gives me hope that some traditions can withstand the homogenizing pressure of commercial sports. Every time I see that specially made ball tossed into the waiting crowd, I'm reminded why I fell in love with studying traditional games in the first place - they preserve something essential about who we are and where we come from, something that polished professional sports often loses in pursuit of profit and perfection.